Pancho Gonzales

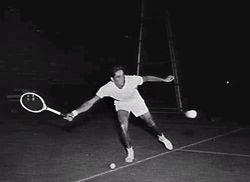

Gonzales practicing in Australia in 1954. |

|

| Full name | Ricardo Alonso González |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Date of birth | May 9, 1928 |

| Date of death | July 3, 1995 (aged 67) |

| Place of death | Las Vegas, NV |

| Height | 1.91 m (6 ft 3 in) |

| Weight | 83 kg (180 lb) |

| Turned pro | 1949 |

| Retired | 1974 |

| Plays | Right-handed |

Ricardo Alonso González (May 9, 1928 – July 3, 1995), generally known as Richard "Pancho" Gonzales (or, less often, as Pancho Gonzalez) was an American tennis player. He was the World No. 1 professional tennis player for an unequalled eight years in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Largely self-taught, Gonzales was a successful amateur player in the late-1940s, twice winning the United States Championships. He is still widely considered to be one of the greatest players in the history of the game. A 1999 Sports Illustrated article about the magazine's 20 "favorite athletes" of the 20th century said about Gonzales (their number 15 pick): "If earth was on the line in a tennis match, the man you want serving to save humankind would be Ricardo Alonso Gonzalez." The American tennis commentator Bud Collins echoed this in an August 2006 article for MSNBC.com: "If I had to choose someone to play for my life, it would be Pancho Gonzalez."[1]

Contents |

Career

Amateur

Gonzales was given a 51-cent racquet by his mother when he was 12 years old. He received some tennis analysis from his friend, Chuck Pate, but mostly taught himself to play by watching other players on the public courts at nearby Exposition Park in Los Angeles. Once he discovered tennis, he lost interest in school and began a troubled adolescence in which he was occasionally pursued by truant officers and policemen. He was befriended by Frank Poulain, the owner of the tennis shop at Exposition Park, and sometimes slept there.[2]

Because of his spotty school attendance and occasional minor brushes with the law, he was ostracized by the overwhelmingly Anglo-Saxon, and predominantly upper-class, tennis establishment of 1940s, which was headquartered at the Los Angeles Tennis Club and which actively trained other top players such as the youthful Jack Kramer. During that time, the head of the Southern California Tennis Association, and the most powerful man in California tennis (and much of the country, given the way weather gave that region a head start in tennis) was Perry T. Jones, described an autocratic leader who embodied much of the exclusionary sensibilities that governed tennis for decades. Although Gonzalez was a promising junior, once Jones discovered that the youth was truant from school, he banned him from playing tournaments[3]

Eventually he was arrested for burglary at age 15 and spent a year in detention. He then joined the Navy just as World War II was ending and served for two years, finally receiving a bad-conduct discharge in 1947.

According to his autobiography, Gonzales stood 6'3" (1.91 m) and weighed 183 pounds (83 kg) by the time he was 19 years old. Other sources generally credit him as being an inch or two shorter but in any case he would enjoy a clear advantage in height over a number of his most prominent rivals, particularly Pancho Segura, Ken Rosewall, and Rod Laver, all of whom were at least 5 or 6 inches shorter. Tony Trabert, who was badly beaten by Gonzales on their 101-match tour and who disliked him intensely, nevertheless once told the Los Angeles Times: "Gonzales is the greatest natural athlete tennis has ever known. The way he can move that 6-foot-3-inch frame of his around the court is almost unbelievable. He's just like a big cat... Pancho's reflexes and reactions are God-given talents. He can be moving in one direction and in the split second it takes him to see that the ball is hit to his weak side, he's able to throw his physical mechanism in reverse and get to the ball in time to reach it with his racket." [4] The flamboyant Gussie Moran, who briefly toured with the Gonzales group, said that watching Gonzales was like seeing "a god patrolling his personal heaven." [5]

In spite of his lack of playing time while in the Navy, and as a mostly unknown 19-year-old in 1947, Gonzales achieved a National Ranking of No. 17 by playing primarily on the West Coast. He did, however, go East that year to play in the United States Championships at Forest Hills. He surprised the British Davis Cup-player Derek Barton, then lost a five-set match to the number-3 seed, Gardnar Mulloy. Following that, in the last major tournament of the year, the Pacific Southwest, played at the Los Angeles Tennis Club, he beat three internationally known names, Jaroslav Drobný, Bob Falkenburg, and Frank Parker, before losing in the finals to Ted Schroeder.

The following year, 1948, Perry T. Jones relented in his opposition to Gonzales and sponsored his trip East to play in the major tournaments. The top-ranked American player, Ted Schroeder, decided at the last moment not to play in the United States Championships and Gonzales was seeded number 8 in the tournament. To the surprise of most observers, he won it fairly easily by a straight-set victory over the South African Eric Sturgess in the finals with his powerful serve-and-volley game. As The New York Times story of that first win began, "The rankest outsider of modern times sits on the tennis throne." His persona at the time was strikingly different from what it would become in future years. American Lawn Tennis wrote that "the crowd cheered a handsome, dark-skinned Mexican-American youngster who smiled boyishly each time he captured a hard-fought point, kissed the ball prayerfully before a crucial serve, and was human enough to show nervousness as he powered his way to the most coveted crown in the world." This was Gonzales's only major tournament victory of the year, but it was enough to let him finish the year ranked as the number one American player.

In 1949, Gonzales did badly at Wimbledon and was derided for his performance by some of the press. A British sportswriter called him a "cheese champion" and, because of his name, his doubles partner of the time, Frank Parker, began to call him "Gorgonzales", after Gorgonzola, the Italian cheese. This was eventually shortened to "Gorgo", the nickname by which he was later known by his colleagues on the professional tour. (Jack Kramer, in his autobiography, says that it was Jim Burchard, the tennis writer for the New York World-Telegram who first called him a "cheese champ".)"[6]

When Gonzales returned to the United States Championships in 1949, once again to the surprise of many observers, he repeated his victory of the previous year. Ted Schroeder, the No. 1 seed, had beaten Gonzales eight times in nine matches during their careers and was heavily favored — the single time Gonzales had beaten Schroeder, he was playing with a nose that had been broken the day before by his doubles partner's tennis racquet during a misplayed point at the net. In a tremendous final that has been called the 11th greatest match of all time",[7] Gonzales lost a 1-hour and 15-minute first set 16-18 but finally managed to prevail in the 5th set. Once again he finished the year as the number-one ranked U.S. amateur. Gonzales also won both his singles matches in the Davis Cup finals against Australia. Having beaten Schroeder at Forest Hills, he was clearly the best amateur in the world. Bobby Riggs, who had been counting on signing Schroeder to play Kramer on the professional tour, was then forced to reluctantly sign Gonzales instead.

Professional

Kramer

Gonzales was badly beaten in his first year on the professional tour, 96 matches to 27, by the reigning king of professional tennis, Jack Kramer. During this time, Gonzales's personality apparently changed from that of a friendly, happy-go-lucky youngster to the hard-bitten loner he became known as for the rest of his life. According to Kramer in his 1979 autobiography, "The worst thing that ever happened to Gonzales was winning Forest Hills in 1949... At a time when Gorgo wasn't mature as a player he was pitted against Kramer, an established pro at his peak." Moreover, says Kramer, "Pancho had no idea how to live or take care of himself. He was a hamburger-and-hot-dog guy to start with and had no concept of diet in training... On the court Gorgo would swig Cokes through a match... Also Gorgo was a pretty heavy cigarette smoker. He had terrible sleeping habits made even worse by the reality of a tour."

Kramer won 22 of the first 26 matches and 42 of the first 50. Gonzales improved enough to win 15 of the remaining 32 but it was too late. Bobby Riggs, the tour promoter, told Gonzales that he was now "dead meat": Kramer would need a new challenger for the next tour. As compensation, however, Gonzales had made $75,000 in his losing efforts. Kramer also said that "his nature had changed completely. He became difficult and arrogant. Losing had changed him. When he got his next chance, he understood that you either win or you're out of a job." He was now "a loner", said Ted Schroeder, "and always the unhappiest man in town." [5]

Semi-retirement

From 1951 to 1953, Gonzales was in semi-retirement. He bought the tennis shop at Exposition Park and ran that while playing in short tours and occasional professional tournaments throughout the world. In spite of his infrequent play (because first Riggs, then Kramer, as promoters of the pro tour, didn't want him as the headliner of their tours), he had nevertheless raised his game to a higher level than before and once again was winning most of his matches. Precise records of this time are difficult to locate but Gonzales asserts in his autobiography that after the decisive loss to Kramer in their 1949-1950 tour he then beat his old antagonist 11 times in their next 16 matches.

In the Southern Hemisphere summer of 1950-1951, Gonzales toured Australia and New Zealand with Dinny Pails, Frank Parker, and Don Budge. In December 1950, Pails won the short tour in New Zealand but in January and February 1951 Gonzales won a second and longer tour in Australia. Though Gonzales also won Wembley (where Kramer was not entered) in the fall of 1951, it is probable that both Kramer and Segura were marginally better players that year. In 1952, however, Gonzales reached the top level of the pros. In 1952 he entered five tournaments and captured four: the Philadelphia Inquirer Masters tournament, where he beat both Segura and Kramer twice in a double round-robin event ; Scarborough, England where he defeated Budge and Segura; Wembley, England again beating Segura and Kramer; Berlin, Germany where Segura and Budge lost again to him; and he was a finalist in the United States Professional Championships ("U.S. Pro") against Segura. In all, Gonzales beat Segura five matches out of six and Kramer three times in three matches. This was the first year that "Big Pancho" (Gonzales) dominated "Little Pancho" (Segura) in their head-to-head matches, and thereafter his superiority over Segura never wavered throughout their long careers.

Although the Professional Lawn Tennis Association issued rankings at the end of 1952 in which they called Segura the World Pro No. 1, with Gonzales 2nd, the PLTA rankings were notoriously quirky — the year before, for instance, when Kramer had beaten Segura 64 matches to 28 (or 58-27 according to Kramer) in their championship tour, they had nevertheless ranked Segura as the World No. 1 player. A strong case can therefore be made that Gonzales was actually the World Pro No. 1 player for 1952 or, at the very least, shared that position with Segura.

At a professional event in 1951, the forehand drives of a number of players were electronically measured. Kramer was particularly known for his fine forehand, but Gonzales was recorded as hitting the fastest one, 112.88 mph, followed by Kramer at 107.8 and Welby Van Horn at 104. Since it was generally assumed at the time that Pancho Segura's two-handed forehand was the hardest in tennis, it is possible that he was not present at that event.[8]

In 1953, Gonzales, drawn aside from the big pro tour by Kramer (by now also a promoter), featuring Frank Sedgman, a seven-time Grand Slam singles winner, Pancho Segura, Ken McGregor (the 1952 Australian Open champion) and Kramer himself, regressed because he had not met a high-level player for 12 months between Wembley 1952 and Wembley 1953. Consequently, in Wembley and two days after in Paris, Gonzales was severely crushed by Sedgman, the future winner of these tournaments.

In late 1953, Kramer, then a temporarily retired player (due to his back troubles), signed Gonzales (a seven-year contract) to play in a 1954 USA tour also featuring Pancho Segura, Frank Sedgman and Donald Budge (the latter being replaced in March 1954 by Carl Earn for the last weeks of the tour). In the subsequent matches Gonzales beat Segura 30-21 and Sedgman by the same score. After this tour Gonzales won the U.S. Pro where all the best, except Pails, were present. Then the American played in a Far East tour (September-October 1954). He barely won over Segura and Kramer, who made his come-back in singles after a 14-month retirement. Then Gonzales had major success: he swept the Australian Tour in November-December 1954 by beating Sedgman 16 matches to 9, McGregor 15 to 0, and Segura, 4 to 2. Although Pancho was beaten by the Australian Pro Pails in the last competition of the year, Gonzales had clearly established himself as the top player in the world in 1954.

Dominance

Gonzales was now the dominant player in the men's game for about the next eight years, beating such tennis greats as Sedgman, Tony Trabert, Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad, Mal Anderson, and Ashley Cooper on a regular basis. Forty years after his matches with Gonzales, Trabert told interviewer Joe McCauley "that Gonzales's serve was the telling factor on their tour — it was so good that it earned him many cheap points. Trabert felt that, while he had the better groundstrokes, he could not match Pancho's big, fluent service."[5]

In that period, Gonzales won the United States Professional Championship eight times and the Wembley professional title in London four times, plus beating, in head-to-head tours, all of the best amateurs who turned pro, which included every Wimbledon champion for 10 years in a row. During this time Gonzales was known for his fiery will to win, his cannonball serve, and his all-conquering net game, a combination so potent that the rules on the professional tour were briefly changed in the 1950s to prohibit him from advancing to the net immediately after serving. Under the new rules, the returned serve had to bounce before the server could make his own first shot, thereby keeping Gonzales from playing his usual serve-and-volley game. He won even so, and the rules were changed back. So great was his ability to raise his game to the highest possible level, particularly in the fifth set of long matches, Allen Fox has said that he never once saw Gonzales lose service when serving for the set or the match.

Trabert and Rosewall

In late 1955 and early 1956 Gonzales beat the athletic Tony Trabert by 74 matches to 27, a series made more compelling by the fact that the two players disliked each other intensely. At the end of 1956 Kramer signed Ken Rosewall to play another long series against Gonzales. In early 1957 Gonzales flew to Australia for the first 10 matches against Rosewall in his native country. Gonzales had developed a "half-dollar"-size cyst on the palm on his right hand and there was speculation in the newspapers that his tennis career might be over. Kramer's personal physician began to treat it with injections, and it gradually began to shrink. It was still painful, however, when Gonzales beat Rosewall in their initial match and eventually won their brief Australian tour 7 matches to 3, with Rosewall beating Gonzales in a tournament whose results did not count towards the series total. By the time the tour opened in New York in late February, the cyst had shrunk considerably and Gonzales went on to beat Rosewall by a final score of 50 matches to 26.

Kramer has written that he was so worried that Rosewall would offer no competition to Gonzales and would thereby destroy the financial success of the tour that, for the only time in his career as a player or promoter, he asked Gonzales while in Australia to "carry" Rosewall in return for having his share of the gross receipts raised from 20 percent to 25 percent. Gonzales reluctantly agreed. After 4 matches, with Gonzales ahead 3 to 1, Gonzales came to Kramer to say that "I can't play when I'm thinking about trying to carry the kid. I can't concentrate. It just bothers me too much." By this time, however, it was apparent that Rosewall would be fully competitive with Gonzales, so Kramer told Gonzales to return to his normal game — and that he could keep his additional 5 percent.

Later that year, Gonzales sued in California superior court to have his 7-year contract with Kramer declared invalid. As proof of his claim, Gonzales cited being paid 25 percent of the gate instead of the stipulated 20 percent. Judge Leon T. David found Gonzales's reasoning implausible and ruled in favor of Kramer. Gonzales remained bound to Kramer by contract until 1960."[9]

Hoad

The most difficult challenge that Gonzales faced during those years came from Lew Hoad, the very powerful young Australian who had won five Grand Slam titles as an amateur. In the 1958 tour, Gonzales and Hoad played head-to-head 87 times. Hoad won 18 of the first 27 matches and it appeared that he was about to displace Gonzales as the best in the world. Gonzales, however, revamped and improved his backhand during the course of those first matches, just as Bill Tilden had to do in 1920 in order to become the best in the world, and then he won 42 of the next 60 matches to maintain his superiority by a margin of 51 wins to 36 wins for Hoad.

Much of Gonzales's competitive fire during these years derived from the anger he felt at being paid much less than the players he was regularly beating. In 1955, for instance, he was paid $15,000 while his touring opponent, the recently turned professional Tony Trabert, had a contract for $80,000. He had an often bitter adversarial relationship with most of the other players and generally travelled and lived by himself, showing up only in time to play his match, then moving on alone to the next town. Gonzales and Jack Kramer, the long-time promoter of the tour, were also bitter enemies dating to the days when Kramer had first beaten the youthful Gonzales on his initial tour. Now they fought incessantly about money, while Kramer openly rooted for the other players to beat Gonzales. As much as he disliked Gonzales, however, Kramer knew that Gonzales was the star attraction of the touring professionals and that without him there would be no tour at all.

Regarding the tour, Kramer writes that "even though Gonzales was usually the top name, he would almost never help promote the Tour. The players could have tolerated his personal disagreeableness, but his refusal to help the group irritated them the most. Frankly, the majority of players disliked Gonzales intensely. Sedgman almost came to blows with Gonzales once. Trabert and Gorgo hated each other. The only player he ever tried to get along with was Lew Hoad."

Trabert also told McCauley in their interview that "I appreciated his tennis ability but I never came to respect him as a person. Too often I had witnessed him treat people badly without a cause. He was a loner, sullen most of the time, with a big chip on his shoulder and he rarely associated with us on the road. Instead he'd appear at the appointed hour for his match, then vanish back into the night without saying a word to anyone. We'd all stay around giving autographs to the fans before moving on to the next city. Not Pancho. But on court he was totally professional as well as a fantastic player."[5] In a 2005 interview, Ted Schroeder commented on Gonzales's intense demeanor both on and off the court, "We hardly ever spoke a civil word to one another, yet we were friends. He was a very prideful man, not proud, prideful. When you understood that, you understood him.[10]

Life on the tour was not easy. "One night", Gonzales recalled later, "I sprained an ankle badly. The next night in another town I was hurting. I told Jack I couldn't play. He said to me, 'Kid, we always play.' Jack had a doctor shoot me up with novocaine, and we played. That's just the way it was. The size of the crowd didn't matter. They'd paid to see us play."[5]

The rigors were not only physical ones. In the 1963 United States Professional Championship, which were held that year at the hallowed Forest Hills courts, Gonzales both dismayed and infuriated his colleagues by being the only player who was paid for his participation. Having learned by bitter experience about the exigencies of the pro tour, Gonzales had demanded, and received, $5,000 in advance for his appearance in the tournament. An out-of-shape, semi-retired Gonzales was beaten in the first round. Ken Rosewall eventually beat Rod Laver in the finals but neither of them collected a penny: the promoter had failed to meet his costs and couldn't pay any of the players.

Open tennis

Most of Gonzales's career as a professional fell before the start of the Open Era of tennis in 1968, and he was therefore ineligible to compete at the Grand Slam events between 1949 (when he turned pro) and 1967. As has been observed about other great players such as Rod Laver, Gonzales almost certainly would have won a number of additional Grand Slam titles had he been permitted to compete in those tournaments during that 18-year period. Jack Kramer, for instance, has speculated in an article about the theoretical champions of Forest Hills and Wimbledon that Gonzales would have won an additional 11 titles in those two tournaments alone.

The first major Open tournament was the French Championships in May 1968, when Gonzales had just turned 40. In spite of the fact that he had been semi-retired for a number of years and that the tournament was held on slow clay courts that penalize serve-and-volley players, Gonzales beat the 1967 defending champion Roy Emerson in the quarterfinals. He then lost in the semi-finals to Rod Laver. He lost in the third round of Wimbledon but later beat the second-seeded Tony Roche in the fourth round of the United States Open before losing an epic match to Holland's Tom Okker.

One of the greatest matches ever played

In 1969, however, it was Gonzales's turn to prevail in the longest match ever played till that time, one so long and arduous that it resulted in the advent of tie break scoring. As a 41-year-old at Wimbledon, Gonzales met the fine young amateur Charlie Pasarell, a Puerto Rican younger than Gonzales by 16 years who revered his opponent.

Pasarell won a titanic first set, 24-22, then with daylight fading, the 41-year-old Gonzalez argued that the match should be suspended. The referee didn't relent and thus the petulant Gonzalez virtually threw the second set, losing it 6-1. At the break, the referee agreed the players should stop. Gonzalez was booed as he walked off Centre Court.

The next day, the serves, the volleys and all the prowess that made Gonzales a fiery competitor surfaced with trademark vengeance. Pasarell, seeking to exploit Gonzalez's advanced years, tried to aim soft service returns at Gonzalez's feet and tire him with frequent lobs. Barked Gonzalez on a changeover, "Charlie, I know what you're doing – and it's not working!" Gonzalez rebounded to win three straight sets, 16-14, 6-3, 11-9. In the fifth set, Gonzales won all seven match points that Pasarell had against him, twice coming back from 0-40 deficits, to walk off the court from the 5-hour, 12-minute epic.[3]

The final score was an improbable 22-24, 1–6, 16-14, 6–3, 11-9. Gonzales went on to the fourth round of the championship, where he was beaten in four sets by Arthur Ashe. The match with Pasarell, however, is still remembered as one of the highlights in the history of tennis and has been called one of "The Ten Greatest Matches of the Open Era" in the November/December 2003 issue of TENNIS magazine.[11] But it was not this match alone which gave Gonzales the reputation, among the top players, of being the greatest long-match player in the history of the game.

The match would (largely due to the introduction of the tie break) remain the longest in terms of games played until the historic, 11 hours and 183 games long Isner–Mahut match at the 2010 Wimbledon Championships.

Final professional years

Roy Emerson, the fine Australian player who won a dozen Grand Slam titles during the 1960s as an amateur when most of the best players in the world were professionals, turned pro in 1968 at the age of 32, having won the French Open the year before. Gonzales, eight years older, immediately beat him in the quarter-finals of the French championships. In the following years, Gonzales beat Emerson another 11 times, apparently losing very few matches to him. In the Champions Classic of 1970 in Miami, Florida, however, Emerson did beat Gonzales in straight sets, 6–2, 6–3, 6–2.[12]

Another great Australian player was Ken Rosewall, who won eight Grand Slam titles during his long career, first as an amateur, then as a professional in the early years of Open tennis. Gonzales played 160 matches against Rosewall, winning 101 and losing 59.

In late 1969, Gonzales won the Howard Hughes Open in Las Vegas and the Pacific Southwest Open in Los Angeles, beating, among others, John Newcombe, Ken Rosewall, Stan Smith (twice), Cliff Richey, and Arthur Ashe. He was the top American money-winner for 1969 with $46,288. If the touring professionals had been included in the United States rankings, it is likely he would have been ranked number one in the country, just as he had been two decades earlier in 1948 and 1949.

Gonzales continued to play in the occasional tournament in his 40s. He could also occasionally beat the clear number-one player in the world, Rod Laver. Their most famous meeting was a $10,000 winner-take-all match before a crowd of 15,000 in Madison Square Garden in February 1970. Coming just after the Australian had completed a calendar-year sweep of the Grand Slams, the 41-year-old Gonzales beat Laver in five sets. He became the oldest player to have ever won a professional tournament, winning the Des Moines Open over 24-year-old Georges Goven when he was three months shy of his 44th birthday. In spite of the fact that he was still known as a serve-and-volley player, in 1971, when he was 43 and Jimmy Connors was 19, he beat the great young baseliner by playing him from the baseline at the Pacific Southwest Open. Around this time, Gonzalez relocated to Las Vegas to be the Tennis Director at Caesars Palace, and he hired Chuck Pate, his childhood friend, to run the Pro Shop.

Gonzales was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame at Newport, Rhode Island in 1968.

Personal and family life

González's parents, Manuel Antonio González and Carmen Alire, migrated from the Mexican state of Chihuahua to the U.S. in the early 1900s. González was born in 1928, the eldest of seven children. Kramer writes that "Gorgo was not the poor Mexican-American that people assumed. He didn't come from a wealthy family, but from a stable middle-class background, probably a lot like mine. He had a great mother and there was always a warm feeling of family loyalty. If anything, he might have been spoiled as a kid. It's a shame he suffered discrimination because of his Mexican heritage". However, according to other sources, Gonzales's father worked as a house-painter and he, along with his six siblings, were raised in a working class neighborhood. In his autobiography, González states, "We had few luxuries at our house. Food wasn't abundant but it was simple and filling, and we never went hungry. Our clothes were just clothes – inexpensive but clean."[13][14]

González had a long scar across his left cheek that, according to his autobiography, some members of the mass media of the 1940s attributed to his being a Mexican-American pachuco and hence involved in knife fights. This was one more slur that embittered González towards the media in general. The scar was actually the result of a prosaic street accident in 1935 when he was seven years old: pushing a scooter too fast, he ran into a passing car and had his cheek gashed open by its door handle. He spent two weeks in the hospital as a result.

Gonzales was referred to as "Richard" by his friends and family. As the child of middle-class Hispanic parents, young Richard was well aware of the social prejudices of his day. He reportedly disliked the nickname "Pancho", as it was a common derogatory term used against Mexican Americans at the time.[15] In the Hispanic community, the nickname "Pancho" is traditionally only given to individuals whose given name is "Francisco".

Although his surname was properly spelled "González", during most of his playing career he was known as "Gonzales". It was only towards the end of his life that the proper spelling began to be used. Kramer, however, writes that one of Gonzáles's wives, Madelyn Darrow, "decided to change his name. Madelyn discovered in the Castilian upper-crust society, the fancy Gonzales families spelled their name with a z at the end to differentiate from the hoi polloi (sic) Gonzales. So it was Gonzalez for a time, and even now you will occasionally see that spelling pop up. I don't think Pancho gave a damn one way or the other."[16] However, that theory is unlikely, as Gonzalez is actually a much more common spelling of that name than Gonzales. In his ghost-written 1959 autobiography, "Gonzales" is used throughout.

Gonzales became a television commentator for ABC, a rare presence at tournaments. Described as an adequate but unmotivated commentator, Gonzales would issue thoughtful comments - often magnanimous, occasionally harsh, always candid - on contemporary pros not unlike an old soldier who'd preferred dying in battle than merely fading away.[3]

For decades Gonzáles had made $75,000 a year from an endorsement contract with Spalding for racquets and balls but was unable to get along with the company personnel. Finally, in 1981, after nearly 30 years, Spalding refused to renew the contract. He had also been the Tennis Director and Tournament Director at Caesars Palace on the Las Vegas Strip for 16 years, another lucrative job. In 1985, he was fired after refusing to give playing lessons to the wife of his boss.[5] As S. L. Price wrote about Gonzáles in a 2002 Sports Illustrated article, "There was no more perfect match than Pancho and Vegas: both dark and disreputable, both hard and mean and impossible to ignore."

Gonzáles married and divorced six times and had seven children: he wed his childhood sweetheart, Henrietta Pedrin, on March 23, 1948; they had three children. He married actress (and Miss Rheingold of 1958) Madelyn Darrow twice; they had three children including twin girls. He married his dental hygienist, Betty, in Beverly Hills and had one daughter. His last wife, Rita, is the sister of Andre Agassi. According to Price's article, Rita's father, Mike Agassi, a 1952 Olympian on the Iranian boxing team who had become a successful casino greeter in Las Vegas, hated Gonzáles so much that he considered having him killed. Gonzáles had coached the young Rita until she had rebelled against her father's 5,000-balls-a-day-regimen and first moved in with, then married, on 31 March 1984, the much older Gonzáles. Years before, Mike Agassi, already a tennis fanatic, had once served as a linesman for one of Gonzáles's professional matches in Chicago. Gonzáles had upbraided Agassi so severely for perceived miscalls that Agassi had walked away and gone to sit in the stands.

Kramer says that "Gonzales never seemed to get along with his various wives, although this never stopped him from getting married... Segura once said, 'You know, the nicest thing Gorgo ever says to his wives is "Shut up". Gonzáles died of cancer in Las Vegas on July 3, 1995, in poverty and almost friendless, estranged from his ex-wives and children except for Rita and their son, Skylar, and daughter, Jeanna Lynn. Andre Agassi paid for his funeral.

Place among the all-time great tennis players

For about 14 years from around 1920 to 1934, Bill Tilden was generally considered the greatest player of all time. From 1934 through 1967, during the Golden Age of Tennis, when Vines, Perry, Budge, Riggs, Kramer, Gonzales, Segura, Sedgman, Trabert, Hoad, Rosewall, and Laver were the top tier players, Gonzales was considered the best of this period. Since 1968, with the first Grand Slam of the Open Era at the French Open, Champions such as Rod Laver, Björn Borg, John McEnroe, Pete Sampras, and Roger Federer have been considered by their contemporaries to be greater players than Tilden or Gonzales.

Many people connected with the game, however, consider Gonzales to be the best male player in tennis history, because he was the World No. 1 tennis player for eight years — the status of a few of the earlier years is still unclear. He was possibly No.1 in 1952, but then was probably the World No.1 for seven consecutive years, 1954 through 1960. In the article World number one male tennis player rankings Bill Tilden with Rod Laver are the next closest to Gonzales with seven No.1 ratings, followed by Pete Sampras and Ken Rosewall with six each. Pancho Segura, who played, and frequently beat, all of the great players from the 1930s through the 1960s has said that he believes that Gonzales was the best player of all time. Lew Hoad and Allen Fox agree with this assessment. In a 1972 article about an imaginary tournament among the all-time greats, Gene Scott had the fourth-seeded Gonzales upsetting Bill Tilden in the semi-finals and then using his serve to beat Rod Laver in the finals.

Bud Collins, the editor of the massive Total Tennis, The Ultimate Tennis Encyclopedia, is guarded. He writes on page 673 that Gonzales was "probably as good as anyone who ever played the game, if not better." On page 693, however, he writes that Rod Laver would "be known as possibly the greatest player ever." And on page 749 he calls Bill Tilden "perhaps the greatest player of them all."

In 2005 a tennis historian who visited the International Tennis Hall of Fame interviewed several great Australian players who had toured against Gonzales. Who, they were asked, was the best player they had ever played against?[17]

Mal Anderson named Gonzales, who "was very difficult since if you did get ahead, he had a way to upset you, and he could exploit your weaknesses fast. Though over the hill, he beat Rod [Laver] until Rod lifted his game." He added, "Lew Hoad, in his day was scary, though Gonzales was best day in and day out." Ashley Cooper also named Gonzales, whom "I never beat on the tour. But I did beat him a couple of times on clay where his serve wasn’t as good." Gonzales's frequent opponent Frank Sedgman said, "I played against probably the greatest of all time, Jack Kramer. He could put his serve on a dime and had a great first volley. The second best was Gonzales. I played him a lot — a great competitor — a great athlete."

Jack Kramer, on the other hand, who became a world-class player in 1940 and then beat Gonzales badly in the latter's first year as a professional, has stated that he believes that although Gonzales was better than either Laver or Sampras he was not as good as either Ellsworth Vines or Don Budge. Kramer, who had a long and frequently bitter relationship with Gonzales, rates him only as one of the four players who are second to Budge and Vines in his estimation.[18] Kramer also, perhaps surprisingly, writes that Bobby Riggs would have beaten Gonzales on a regular basis.

Early in 1986 Inside Tennis, a magazine published in Northern California, devoted parts of four issues to a lengthy article called "Tournament of the Century", an imaginary tournament to determine the greatest of all time. They asked 37 tennis notables such as Kramer, Budge, Perry, and Riggs and observers such as Bud Collins [19] to list the 10 greatest players in order.

Twenty-five players in all were named by the 37 experts in their lists of the 10 best. The magazine then ranked them in descending order by total number of points assigned. The top eight players in overall points, with their number of first-place votes, were: Rod Laver (9), John McEnroe (3), Don Budge (4), Jack Kramer (5), Björn Borg (6), Pancho Gonzales (1), Bill Tilden (6), and Lew Hoad (1). Gonzales was ranked the sixth-best player, with only Allan Fox casting a vote for him as the greatest of all time.

Performance timeline for major tournaments

As amateur player Pancho Gonzales won at least 17 singles titles, including 2 Grand Slam tournaments. As professional player he won at least 85 singles titles, including 12 Pro Slam tournaments; at the same time he was banned to compete in the Grand Slam events. During this professional period he won 7 times the World Pro Tour'. The Open Era arrived very late to Gonzales when he was in his early forties. Even at this advanced age he was able to win at least 11 singles titles. Overall Gonzales won at least 113 titles in his succesfull career in a span of 25 years.

Performance Timeline:

| Titles / Played | Career Win-Loss | Career Win % | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Slam Tournaments | Amateur | Professional | Open Era | 2 / 17 | 43-15 | 74.14 | |||||||||||||||

| 1947 | 1948 | 1949 | 1950 - 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | ||||||||||||

| Australian | A | A | A | Unable to compete | 3R | A | A | A | A | 0 / 1 | 2-1 | 66.67 | |||||||||

| French | A | A | SF | Unable to compete | SF | A | A | A | A | A | 0 / 2 | 9-2 | 81.82 | ||||||||

| Wimbledon | A | A | 4R | Unable to compete | 3R | 4R | A | 2R | 2R | A | 0 / 5 | 10-5 | 66.67 | ||||||||

| U.S. | 2R | W | W | Unable to compete | QF | 4R | 3R | 3R | 1R | 1R | 2 / 9 | 23-7 | 76.67 | ||||||||

| Pro Slam Tournaments | Professional | 12 / 26 | 60-14 | 81.08 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | ||||

| French Pro | NH | F | NH | SF | A | A | F | A | A | SF | A | A | A | 0 / 4 | 7-4 | 63.64 | |||||

| Wembley Pro | W | W | W | F | NH | W | SF | SF | A | A | SF | A | A | SF | A | A | A | 4 / 9 | 22-5 | 81.48 | |

| U.S. Pro | A | 2nd | F | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | A | W | A | QF | F | SF | A | A | 8 / 13 | 31-5 | 86.11 |

| Total: | 14 / 43 | 103-29 | 78.03 | ||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ The Collins article: http://msnbc.msn.com/id/14489546/

- ↑ Man with a Racket, The Autobiography of Pancho Gonzales (1959), page 26

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/hispanicheritage2008/news/story?id=3604713

- ↑ Man with a Racket, The Autobiography of Pancho Gonzales, as Told to Cy Rice (1959), page 129

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 The Lone Wolf, by S. L. Price, Sports Illustrated, June 26, 2002

- ↑ The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis (1979), Jack Kramer with Frank Deford (ISBN 0-399-12336-9), page 177

- ↑ Tennis Magazine, on page 330 of The Tennis Book, Edited by Michael Bartlett and Bob Gillen

- ↑ The History of Professional Tennis, Joe McCauley, page 57

- ↑ All information about the Australian tour with Rosewall is from The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis, pages 225-228

- ↑ Legend ignored? | The San Diego Union-Tribune

- ↑ The 10 Greatest Matches of the Open Era [Archive] - TennisForum

- ↑ World of Tennis Yearbook 1971, by John Barrett, page 142

- ↑ http://sports.jrank.org/pages/1666/Gonzales-Richard-Pancho-Taught-Himself-Play.html

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=oeQiAAAAMAAJ&q=pancho+gonzales+%22we+had+few+luxuries%22&dq=pancho+gonzales+%22we+had+few+luxuries%22&ei=diBfSdGbHJXSlQSymNRC&pgis=1

- ↑ Hispanic Magazine.com - Nov 2006 - The Latin Forum

- ↑ The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis (1979), Jack Kramer with Frank Deford (ISBN 0-399-12336-9), page 201

- ↑ Interviews by tennis historian Rich Hillway in 2005 at the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

- ↑ In his 1979 autobiography Kramer considered the best ever to have been either Don Budge (for consistent play) or Ellsworth Vines (at the height of his game). The next four best were, chronologically, Bill Tilden, Fred Perry, Bobby Riggs, and Pancho Gonzales. After these six came the "second echelon" of Rod Laver, Lew Hoad, Ken Rosewall, Gottfried von Cramm, Ted Schroeder, Jack Crawford, Pancho Segura, Frank Sedgman, Tony Trabert, John Newcombe, Arthur Ashe, Stan Smith, Björn Borg, and Jimmy Connors. He felt unable to rank Henri Cochet and René Lacoste accurately but felt they were among the very best.

- ↑ The 37 were: Vijay Amritraj, Arthur Ashe, Lennart Bergelin (Björn Borg's coach), Nick Bollettieri, Norm Brooks, Don Budge, Nick Carter, Bud Collins, Allison Danzig, Donald Dell, Cliff Drysdale, Allan Fox, John Gardiner, Dick Gould, Slew Hester, Bill Jacobsen, Alan King, Jack Kramer, Art Larsen, Rod Laver, Bob Lutz, Barry MacKay, Marty Mulligan. Yannick Noah, Manuel Orantes, Charlie Pasarell, Fred Perry, Whitney Reed, Bobby Riggs, Vic Seixas, Stan Smith, Bill Talbert, Eliot Teltscher, Ted Tinling, Tony Trabert, Dennis van der Meer, Erik van Dillen.

Sources

- The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis (1979), Jack Kramer with Frank Deford (ISBN 0-399-12336-9)

- The History of Professional Tennis (2003), Joe McCauley

- Man with a Racket, The Autobiography of Pancho Gonzales, as Told to Cy Rice (1959)

- Rich Hillway, tennis historian - Q&A with the Aussies

- The Tennis Book (1981), Edited by Michael Bartlett and Bob Gillen (ISBN 0-87795-344-9)

- The Lone Wolf, by S. L. Price, Sports Illustrated, June 26, 2002

- World of Tennis Yearbook 1971 (1971), by John Barrett, London

External links

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||